Our Route:

2019 Oslo-Toulouse

-

Recent Posts

Articles & CBC Podcast

Archives

- Follow Chris and Margo's Wanderings on WordPress.com

Our Route:

Posted in Bangkok to Paris 2009, Bike Touring, Central Asia, China, Europe, Southeast Asia

Daily Distances:

The histogram shows the distribution of daily distances ridden. The days on which we rode 40 km or less are not what we’d really call “travelling days,” but are more the type of day on which we get ourselves to a particular target destination. Sometimes the days of only 10 or 20km involved getting to a ferry or doing local sightseeing and errands.

The distances of 70–110 km form the crest of something resembling a normal (or is it poisson?) distribution, tapering to the right at our record 177 km day. This longest day was in a crosswind in Xinjiang province, China. If you look at the photo of me with the two Uyghur fellows upon our arrival that evening at their construction camp, (Desert Winds) you’ll see one very tired old lady.

Elevation Profile:

Chris created the profile above from the GPS data he collected. For sections where we were being transported by taxi, bus, or boat, the GPS sometimes wasn’t in operation, so Chris approximated the route on the Garmin world map.

Somehow, we managed to take “other transportation” downhill more often than uphill. Oh well ….I guess it was good for the old legs.

The bump at about 1,000 km is the passes of northern Thailand. The peaks between 2,000 and 3,500 km is the hills of Yunnan and Sichuan provinces. You can see that when we were sent away from a politically sensitive area (Goodbye Yak Butter Tea) and took a bus to Chengdu, we dropped more than 1,500 m. Shaanxi and Gansu provinces involved climbs, and there was a drop to below sea level in the Turpan Basin of Xinjiang at 7,000 km. We confess that we took a taxi 2,200 m uphill on road under construction in Kygyzstan, as we dashed from Osh to Sary Tash and the Tajik border. The highest peak at 4,655 m is Ak-Baital Pass on the Pamir Highway in Tajikistan (10,000 km). The taxi ride (in red) from Khorog to Dushanbe lost us 2,500 m, and took us over three major passes which don’t appear on the profile, not to mention saving us from possible hold-up by corrupt army patrols. Turkey (14,000–16,000 km) has some pretty high country, but the bus to Ankara in the middle of that section also lost elevation. In the scheme of all our ups and downs, the pass that took us across the Austrian Alps (18,500 km) was really pretty inconsequential!

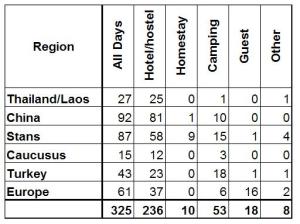

Accommodation:

We travelled for 325 days. Although we were equipped to camp, we stayed in a wide range of accommodation from hotels to hostels to self-catering apartments, or in the simple homestays in Central Asia which are part of their community-based tourism initiatives. We were invited guests in Tajiksitan, Turkey, and mainly in Europe where we have a number of welcoming friends. We camped a total of 53 nights. In China, camping only became an option once we reached the desert regions. We camped most often in Turkey, in both absolute and relative terms. We were there in August and September, and the terrain was inviting. The “other” category involves sleeping (or trying to sleep) in places such as on boats or buses, or on the floor of a ferry terminal.

We’ve been home just over a month, and we’re really appreciating our own comfy bed.

M & C

Posted in Bangkok to Paris 2009, Bike Touring, Central Asia, China, Southeast Asia

We could write a wrap-up blog post describing “what we’ve learned” on our journey, but we realize what hits us may seem trite and obvious to most of our blog audience: People who have little are generous to strangers, borders are rarely logically located, Europe is very small compared to Asia, the Alps aren’t as high as the Pamirs, and the food is delicious in France.

Instead, we’ll tell a bit more of what actually happened but which we did NOT write about at the time. We glossed things over or selectively omitted things from the blog as they happened.

Police Encounters in China

Our first police check was in Yunnan Province in February, and we described it in An Encounter with the Police. Chris took a cheerful photo of me with me and the two uniformed traffic policemen, but the non-uniformed fellow who can be seen beating a hasty retreat to the vehicle was the one who photographed our passports, and was a member of the Public Security Bureau. What I described in the blog as their “concern for our safety on narrow roads” was only a thin pretense for finding out more about our motives and intended movements.

Our policy – which we’d discussed beforehand – was to be completely forthright with them about our intended travel direction, because we know they are very suspicious of cyclists whose movements they’re less able to control and monitor than those of travellers who must take public transportation. Some cyclists succeed in entering Tibet without travel permits by slipping under barricades at night. We did not intend to do this, so handed them a card with our blog address. We knew from the Google Analytic that the blog was visited from the prefecture capital a few days later, and that we were soon being followed by a black car with the driver talking on his cell phone.

In March in Sichuan Province, we had quite a few more police encounters, which we deliberately under-reported on the blog. After the area we were in was closed to foreigners, I wrote in Goodbye Yak Butter Tea of the prefecture boundary incident where “we encountered a larger and better-equipped police presence.” The correct interpretation of this careful euphemism is that there were an awful lot of machine guns and even some artillery on hand.

In the blog I wrote of the later hotel incident:

“The PSB contacted us in our hotel room quite some time later.”

Contrast this wording with the private email we wrote:

“We tried to get the hotel to contact the PSB for us, so we could ask about our options, but they couldn’t or wouldn’t. Perhaps this is because the PSB contacts you. We went went to bed.

The knock came at midnight. In came three PSB guys and a hotel person. Passports examined. “Go back to where you came from” says Mr. Fatso. Do you mean Yunnan, Laos, Thailand, or Canada, I mutter? He repeats his dismissive command. I show the map. Can we go here? No. There? No. Chengdu? Yes, the bus leaves at 6:30 a.m.. So, we set our watches for 5:00 a.m. and pedalled to the bus station. There are a lot of police and army guys along the road to Chengdu, and trucks full of army personnel moving west toward Tibet once we joined the main road. The midnight visit is designed to be intimidating, and it is.”

We were unable to go back to sleep that night, and felt quite shaken as we rode the bus toward Chengdu. We also saw water canons being moved west towards Tibet. Our bus stopped at a military roadblock outside Chengdu, and a woman officer boarded so as to grill us (the only) foreigners about our movements. As she did so, another soldier with his machine gun at the ready stood in the aisle of the bus in case we should decide to try to run off.

As Canadians, we assume we have basic civil liberties, and we found it intimidating to be asked repeatedly if we were journalists. Our concern was such that I went as far as to ask a bicycle magazine in Vancouver remove my contributor’s page from their website, because I’d written some innocuous articles for them on a volunteer basis. We didn’t think the PSB was too likely to differentiate one type of writing from another, suspected they could and would use Google, and knew we needed visa renewals if we wanted to reach Central Asia. We also asked friends to refrain from making any comments on our blog that could possibly be construed as political, enabled comment moderation, filtered some comments, and made sure certain private emails describing the situation were deleted from the Asus computer we were carrying. We felt uncomfortable in Internet cafes when “staff” would hover behind us as we wrote to family and friends.

There was another police encounter just as we were being shown the factory that makes cypress walking sticks between TianShui and Wushan in eastern Gansu Province. A car load of Public Security Police stopped to make sure we weren’t going to go “on that road.” Well, “that road” had been carefully omitted from our paper map even though it showed on the GPS, and there was a military presence where it turned off, so it was unlikely we’d be going that way. However, if I were an investigative journalist looking for a place that held political prisoners for use as involuntary organ donors, I’d certainly have a good idea where to start snooping.

Access to this blog was blocked in China – along with all of blogspot – about the time we crossed to Kazakhstan, so our cycling friends in Chengdu and Lanzhou cannot read of our travels. Chinese citizens must be “protected” from avenues of communication through which political subversion might foment. I’ve just read on BBC news that “China wants to meter all internet traffic that passes through its borders, it has emerged. “ There is discussion of wanting to charge for international data traffic. I’m no techno-whiz, but a technique for metering traffic is surely closely tied to a technique for decoding data. I don’t believe for a minute that the primary motive is financial but rather is political and strategic. Big Brother has a very long arm in China, and would like to extend its reach even further by enhancing its monitoring capabilities.

Feeling we were at the mercy of Big Brother’s long arm was was new to us, and it was not a nice feeling.

Strong Military Presence in Eastern Turkey

We under-reported this aspect of Eastern Turkey so as not to raise undue alarm at home. We only briefly mentioned the military presence and our backtracking due to Kurdish separatist insurgency ahead. There were actually barracks, manned checkpoints, and troop trucks everywhere. The military presence was huge.

In China, our self-censorship stemmed from the feeling of being watched and potentially judged as undesirables. In Turkey, on the other hand, we self-censored for the benefit of home-front readership. We were at some risk of being caught in the crossfire between the Turkish military and Kurds. These latter would stop their vehicles to tell us very firmly that we were in “Kurdistan” – their homeland. We weren’t too disappointed to leave the tense atmosphere when we had to take the bus to Ankara, having discovered my passport was missing.

Whether or not our readership worried about us at the time, we were a bit worried about ourselves.

M

In addition to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan photo sets already uploaded, we’ve now added sets to Flickr for Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. This completes our Cycling Central Asia 2009 Collection. We’ll add labels and geo-tags at some point. Our next photo collection will be called “Azerbaijan, Georgia, & Turkey,” and the final one of our journey will be “Europe.”

Onward we jolly well go!

For us as appreciators of landscapes, Tajikistan stands out in our memories. For those who are interested in architecture, we think the Uzbekistan photos will appeal. Some of the photos of Turkmenistan were snapped from the car window as we raced across hot desert, but our visit to Merv was memorable.

M&C

Posted in Bangkok to Paris 2009, Bike Touring, Central Asia

2009/07/26: Jeep from border to Merv

We began the border crossing process when it opened at 7:00 a.m., finding there was some order on the Uzbek side, but next to none on the Turkmen. We emerged to find our car and driver just after 9:00, and with only front wheels removed our bikes fit neatly in the back of the Toyota mini-van. We were driven to Merv, and deposited at a Soviet-era hotel frequented by Turkish truck drivers. We had lunch, a shower, and a rest, leaving again at 5:00 p.m. once the the heat was a bit less overwhelming, we were driven to see the Merv archaeological site. It covers an extended area, and would be impossible to see without a vehicle. I hummed the theme song from Raiders of the Lost Ark as we rode from one vestige of ancient civilization to another.

2009/07/27: Jeep to Ashgabat

The following day took us to Ashgabat, the capital. My comment as we arrived was “This looks like Burnaby.” Coming in from the desert, it seems incongruously tidy and manicured, with miles of watered green lawn between grandiose but sterile buildings, flagpoles, and fountains. We walked from our hotel to the museum, and were berated by the gardeners for taking an obvious shortcut across the tidy lawn. Grass is only for admiring here. The vaulted museum has three great wings: archeology, natural history, and an entire wing devoted to idolizing Turkmenbashi, the self-appointed leader-for-life.

The only other visitors to the vast museum were a small group of Brits in business suits. We found ourselves leapfrogging them around the archeology wing, and considered moving a bit closer to benefit from their English-speaking guide, but something about the cameraman quietly trailing them prompted us to keep our scruffy selves at a polite distance. Later, we spoke to one of their peripheral figures and learned that the portly central figure was none other than Prince Andrew, on a “private trip.” After getting over our initial surprise, we speculated that Andrew might actually be useful in making initial contact with rogue figures such as the Turkmenbashi, when more mainstream channels aren’t yet functioning. Or perhaps it was just a quick side trip on his way to or from a visit to his Kazakh mafia-connected girlfriend.

We spent some time in the natural history wing, getting a glimpse of all the nasty beasts we were lucky not to have met in the desert. We spent the last few minutes before closing time in the Turkmenbashi wing, trying not to giggle at the over-the-top kitch. There were floor-to-vaulted-ceiling portraits of the current Turkmenbashi, the illegitimate son of the first one, in iconic patriotic settings and poses: riding an akal-teke horse while dressed in national costume, making plov in front of a yurt, surrounded by flag-waving children and so forth. Did we want to see the second floor, we were asked? No thank you, it’s too near closing time. We noticed that HRH Andrew and Co. didn’t visit the the Turkmenbashi wing. Sensible them.

2009/07/28: Jeep to Turkmenbashi

Our driver appeared at the appointed 7:00 a.m. with a different vehicle, and our precious bikes now strapped to the roof. He spoke only Russian and made little effort to communicate, so we never found out why the switch. Alarmed, we checked his bike loading and tying, deeming it OK. He drove us to Turkmenbashi in seven hours. The only excitement as we drove through bleak desert and scrub was camels. Here we see dromedaries rather than the two-humped bactrian camels of Xinjiang, Kazakhstan and Afghanistan. They’re domesticated, and we see them grazing in groups as well as working. Sometimes the loose ones are hobbled. They make me think of a smoothly-moving long-legged brontosaurus, and I see how they earn their nickname of “Ships of the Desert.”

Arriving at the ferry terminal in Turkmenbashi, our driver was unable to find out anything about the next crossing. He drove us to town to buy food and water, and returned to leave us to the whims of a non-existent system for getting across the Caspian.

M

Posted in Bangkok to Paris 2009, Bike Touring, Central Asia, Travel by Car, Turkmenistan

Tagged UNESCO World Heritage Site